🎧 Easy Listen - Audio Deep Dive

At 5:40 p.m. on May 5, 1945, as vacationers strolled the beaches near Point Judith Lighthouse, a German torpedo tore through the hull of the SS Black Point just miles offshore. The war in Europe was officially over. Someone forgot to tell U-853.

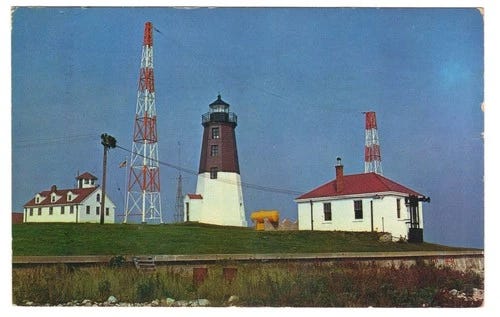

Sixteen years later, a postcard would capture this same lighthouse in perfect summer tranquility. The scene presented visitors to Narragansett, Rhode Island, with a contrast to the violent history of these waters.

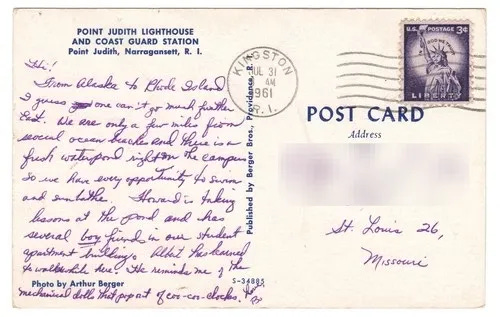

The sender, identified only as "B.", penned a cheerful, unassuming message. The note reflects the simple pleasures of a vacation: "From Alaska to Rhode Island I guess one can't go much further East." "B." describes being "only a few miles from several ocean beaches" and enjoying "a fresh water pond right on the campus so we have every opportunity to swim and sunbathe." The intimate details of family life, with Howard taking lessons at the pond and young Albert learning to walk, likened to "mechanical dolls that pop out of coo-coo clocks," reflect normal vacation activities. Like many visitors, the sender saw only Point Judith's calm waters.

Unknown to "B." and the countless others enjoying Point Judith's calm façade, these very waters were the stage for one of the final, most intense naval engagements of the war in U.S. waters. The tranquility of 1961 concealed a history of conflict and loss, showing how visitors experience places differently than their history suggests. This enduring symbol of coastal safety once bore witness to a final act of war, a story that, despite its significance, has largely receded from common knowledge.

The Lighthouse's Enduring Watch

For over two centuries, the Point Judith Lighthouse has served as a crucial navigational aid along a dangerous stretch of the New England coastline.1 Established in 1810 and rebuilt in 1857, its powerful beacon marked the hazardous confluence where Narragansett Bay meets Block Island Sound.1 Mariners historically referred to this area as a "Graveyard of the Atlantic" due to its cold, rough waters, frequent fog, and dangerous rocky shoals, conditions that contributed to numerous shipwrecks throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.1

The grounds around the lighthouse have hosted Coast Guard activity since the late nineteenth century, with a station first built in 1876 and rebuilt in 1888-1889.3 By 1961, the year the postcard was sent, the Point Judith Coast Guard station was actively involved in frequent search and rescue missions, reflecting the heavy shipping traffic and the region’s unpredictable weather. The distinctive radio beacon towers, clearly visible on the 1961 postcard, represented a technological advancement of their time, providing essential guidance for mariners before evolving navigation systems led to their removal in the 1970s.

The Point Judith Lighthouse, a steadfast symbol of safety and vigilance, overlooked the dramatic events that unfolded just miles offshore.5 Its light, designed to prevent disaster and guide vessels to safety, shone over waters where a final, desperate act of war played out. The wreck of U-853 lies approximately 8 miles southeast of Point Judith, a short distance from the lighthouse's guiding beam.5 This enduring structure, built to protect, observed a moment of profound destruction, showing how war reached even peaceful places.

The Unheeded Order

As May 1945 dawned, World War II in Europe was rapidly drawing to a close. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker on April 30, and Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, appointed as his successor, was engaged in negotiations for Germany's unconditional surrender.13 In a pivotal moment, on May 4, 1945, at 5:30 a.m. Eastern Time, Dönitz issued a radio communiqué to all German U-boats: "Cease fire at once. Stop all hostile action against Allied shipping. Dönitz".5 This order was set to take effect at 8:00 a.m. Berlin time on May 5.13

Despite this clear directive, German U-boat U-853, a Type IXC/40 submarine, continued its patrol off the U.S. East Coast.13 Under the command of 24-year-old Lieutenant Helmut Frömsdorf, U-853 was on its third war patrol, having been sent to harass American coastal shipping.6 Just weeks earlier, on April 23, 1945, U-853 had sunk the USS Eagle 56 patrol boat near Portland, Maine.6

The central historical question surrounding U-853's final actions remains: Did Lieutenant Frömsdorf receive Dönitz's cease-fire order, or did he deliberately choose to ignore it? The available historical record does not definitively answer this.5 Some historians suggest he may not have received the message, possibly due to damaged radio equipment or his operational practice of staying submerged to avoid Allied detection, which would limit radio contact.18 Others argue that Frömsdorf, described as a "young and ambitious" commander, may have chosen to defy the order, driven by fanaticism or a desire for a final, personal strike.13 Regardless of his motivations, U-853 remained active, prowling the waters off Rhode Island as the war in Europe drew to its official close.13

5:40 PM: The Final Strike

On the afternoon of May 5, 1945, the SS Black Point, a 368-foot, 5,000-ton coal collier, was on the final leg of its journey from Newport News, Virginia, to Weymouth, Massachusetts, laden with 7,500 tons of coal.13 The ship, built in 1918, was rounding Point Judith, heading into the western end of Rhode Island Sound.13 While some accounts describe fair weather conditions with good visibility near Point Judith 24, the ship had earlier encountered a thick fog bank near New Haven, Connecticut, which had forced Captain Charles Prior to anchor and wait for it to lift.15 Captain Prior was navigating a coastal route and, like many at the time, did not anticipate a significant U-boat threat in these "presumably friendly waters".13

At approximately 5:40 p.m., U-853, from periscope depth, fired a single torpedo at the Black Point.13 The torpedo struck the Black Point's starboard stern, just aft of the engine room.13 The impact was catastrophic. The explosion tore away about 40 feet of the Black Point's stern, along with its 6-pounder gun.13 Captain Prior recounted the immediate aftermath to the Providence Journal years later: "I don't mind telling you that it hit the fan all right. The main mast went over the port side, and about everything on the bridge that was breakable did break. The vibration and concussion was really something. It blew open both doors of the pilothouse".23 The ship shuddered violently, power was cut, and a wave of ocean water rushed in from the stern.16 Captain Prior immediately gave the order to abandon ship. The mortally wounded collier quickly filled with water and began to settle, rolling over twenty-five minutes later and sinking stern first.13

Twelve of the 46 men on board the Black Point perished in the attack, either killed by the blast or drowned as the ship went down.13 Merchant seaman Howard Locke, one of the 34 survivors, vividly recalled watching his ship disappear: "It stood straight up and the last thing I saw was the belly of it".16 The sinking of the Black Point marked the last U.S.-flagged merchant vessel lost to a German U-boat in World War II.13 This event, occurring just days before Germany's surrender, highlights the persistent human cost of war until its very last moments.

The attack was witnessed by nearby vessels, including the Yugoslav freighter SS Kamen, which quickly sent out an SOS, alerting naval authorities to the presence of a hostile submarine.13 From the Point Judith Coast Guard Station, Boatswain’s Mate Joe Burbine also heard the muffled explosion and observed the Black Point through his binoculars, immediately radioing the incident.13 This rapid reporting initiated an immediate and intensive response from U.S. Navy and Coast Guard forces.6

The Hunt Begins

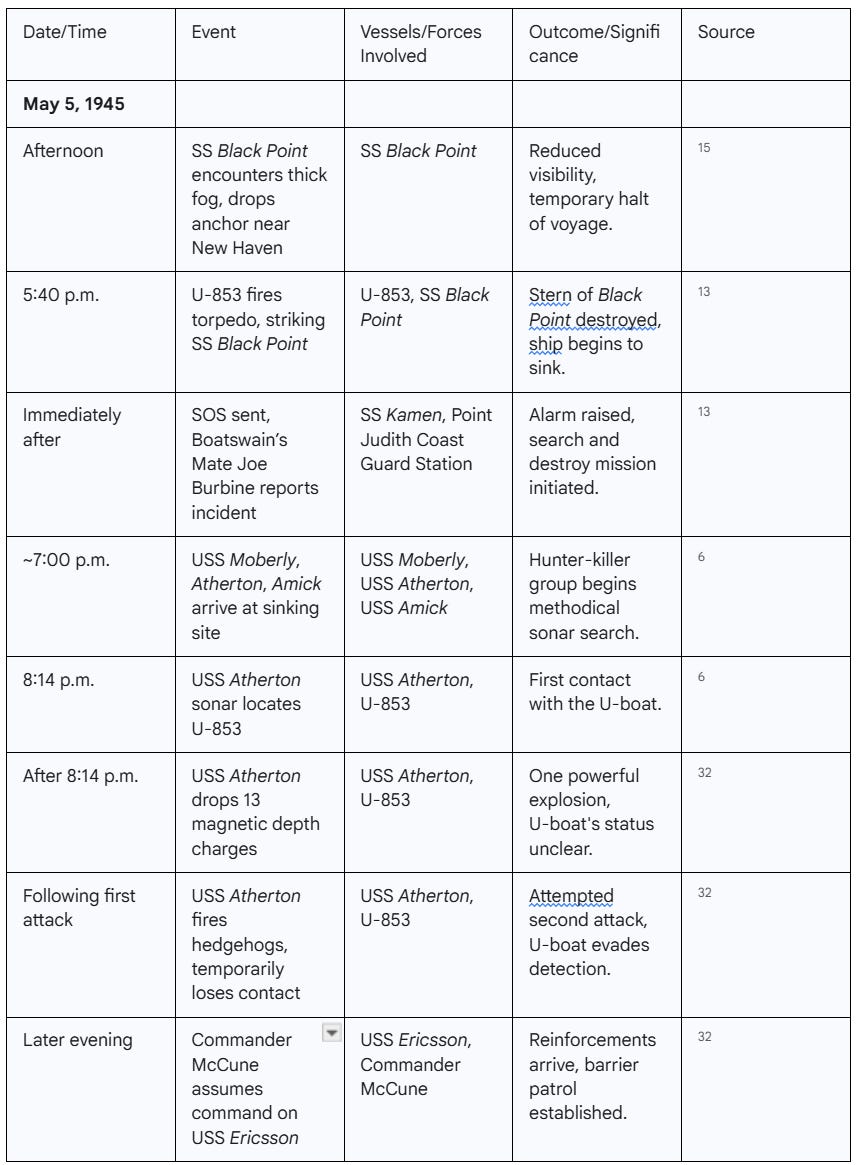

The alarm raised by the Black Point's sinking immediately galvanized U.S. naval forces. The Coast Guard patrol frigate USS Moberly (commanded by Lieutenant Commander L. B. Tollaksen) and destroyer escorts USS Atherton (under Lieutenant Lewis Iselin) and USS Amick were approximately 30 miles southeast of the Black Point's position, en route to Boston after escorting a convoy.32 They were swiftly ordered to change course and steam at full speed toward the site, arriving around 7:00 p.m..6 Commander F. C. McCune, Tollaksen’s superior, arrived later on the destroyer USS Ericsson and assumed overall tactical command.32

The search began with the ships forming a patrol line abreast, methodically sweeping the area with sonar.6 At 8:14 p.m., Atherton's sonar operators located the submarine, approximately five miles east of Grove Point on Block Island.13

Atherton's commander, Lieutenant Iselin, ordered the release of thirteen magnetic depth charges. One exploded with a powerful concussion, though it was unclear if it directly struck the submarine or an old wreck.32 A second attack followed immediately using hedgehogs, forward-firing projectiles designed to detonate only on contact, thus minimizing interference with sonar.6 Atherton temporarily lost contact with the U-boat after this initial barrage.32

Lieutenant Frömsdorf, instead of surfacing and attempting a high-speed escape, chose to remain submerged, moving slowly. This decision was likely influenced by the fear of swift air and sea reactions from nearby naval bases.32 U-853 also employed a common U-boat tactic: releasing oil and debris to create the illusion of destruction and deceive its pursuers.13

However, at 11:37 p.m.,Atherton's sonar re-established contact, locating U-853 lying still at a depth of about 109 feet.13 Another hedgehog attack followed, bringing "Large quantities of oil, life jackets, pieces of wood, and other debris, and air bubbles, coming to the surface".13

Despite the rising debris, the U.S. forces, aware of U-boat deception tactics, continued their relentless assault through the night.13

Moberly's sonar detected U-853 moving again, steering south at a reduced speed of four to five knots.32 Both Atherton and Moberly dropped more depth charges around 12:44 a.m. on May 6. Their spotters recovered more debris, including a pillow, a life jacket, and a small wooden flagstaff.32 Kenneth Homberger, serving on Atherton later recalled, "We always played tag out there with those subs, but we never really knew if we nailed one of them. This time we knew".32 This sentiment reveals the psychological toll of prolonged anti-submarine warfare, where confirmed kills were rare and often uncertain.

With the arrival of daybreak on May 6, two Navy blimps, K-16 and K-58, dispatched from Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, joined the hunt.15 They quickly located oil slicks, marked suspected U-boat positions with smoke and dye, and used Magnetic Anomaly Detection (MAD) radar technology to pinpoint the stationary underwater target.15 The blimps also deployed sonar devices, and operators reported hearing a "rhythmic hammering on a metal surface," a chilling sound that suggested a desperate attempt at repair or communication from within the crippled submarine.32 This detail provides a haunting glimpse into the final moments of the trapped crew.

The Moberly and Ericsson continued their attacks, with blimp K-16 also firing 7.2-inch rocket bombs.32 Around 5:30 a.m., another hedgehog attack from

Moberly brought conclusive evidence to the surface: "German escape lungs and life jackets, several life rafts, abandon-ship kits, and an officer’s cap which was later judged to belong to the submarine’s skipper".13 The intense, 16-hour battle finally ceased at 12:07 p.m. on May 6, when Commander McCune convinced headquarters in Boston that U-853 had been destroyed.32 The sheer volume of ordnance expended—264 hedgehogs, 195 depth charges, and 6 rocket bombs—shows the intensity of this final battle.32

The battle unfolded with methodical precision across sixteen hours:

The Wreck That Remains

U-853 was ultimately destroyed sometime between midnight and 5 a.m. on May 6, 1945.32 All 55 crewmen aboard perished with their vessel, making it a complete loss of life.5 The USS Atherton and USS Moberly were officially credited with the sinking.6 The wreck of U-853 now rests in 110-130 feet of water, approximately 8 miles southeast of Point Judith.5

In the hours following the battle on May 6, a diver from the submarine rescue vessel USS Penguin, which arrived from New London, located the wreck of U-853.5 The diver reported that the submarine lay on its side with its hull split open, revealing bodies strewn inside.5 Navy divers attempted to enter the wreck to recover the submarine commander's safe and papers, possibly even an Enigma coding machine.5 However, Navy brass called off recovery operations due to the imminent signing of Germany's surrender on May 7 and the significant danger posed by unexploded ordnance scattered around the site.5

The U-853 wreck is designated as a war grave, and federal law now prohibits disturbing it.6 Despite this, in the decades following the war, the wreck became a magnet for unauthorized divers and salvage crews.5 In 1960, a recreational diver controversially recovered the skeletal remains of a German crewman, identified as "Hoffman".5 This act sparked public outrage and led to the sailor being buried with full military honors in Newport's Island Cemetery Annex, where his grave can still be seen today.5 Other artifacts, including the submarine's propellers and a deck gun, were also removed from the site over time.5

Today, the U-853 wreck remains a popular, albeit dangerous, dive site, with at least three recreational divers having lost their lives exploring its interior.9 Nautical charts for the area continue to carry a stark warning: "Danger unexploded depth charges, May 1945" 15, a tangible reminder of the intense battle fought there. Locally, the sinking of the Black Point left a more immediate, tangible mark. Residents along the southern Rhode Island coastline, such as Janet Carpenter Vanderlaan, recall the "excitement" in areas like Perryville, Matunuck, and Green Hill, caused by the coal ship's sinking, and how they would go to the beaches to collect coal that had washed ashore from its cargo in the days after the attack.7 These physical remnants and local memories serve as a direct connection to a broader conflict, demonstrating how major historical events can leave lasting imprints on civilian landscapes and lives.

The Story Beneath the Surface

The 1961 postcard from "B." to the Hawkins in St. Louis, Missouri, offers a snapshot of Point Judith as a peaceful, inviting coastal destination. For "B." and countless other visitors, the waters off Point Judith were simply a backdrop for summer recreation—swimming, sunbathing, and family moments. Unaware of the profound history hidden beneath the waves, they experienced only the tranquil surface of a place with a dramatic past. The postcard, in its very innocence, shows that every seemingly ordinary place can have unexpected histories.

The Battle of Point Judith, a significant event as the last naval engagement of World War II in U.S. waters, is not widely known to the general public today. Several factors contributed to this fading memory. The sheer magnitude of Germany's unconditional surrender on May 7-8, 1945, just two days after the battle, immediately overshadowed individual engagements.7 The national focus quickly shifted to victory celebrations, demobilization, and the transition to peacetime, pushing the details of late-war actions out of the immediate public consciousness.43

During the war, information regarding U-boat sinkings near the U.S. coast was often controlled or suppressed to maintain public morale and prevent panic.45 While U-853's sinking was reported by local and national newspapers immediately after the event 7, the narrative quickly moved on to the broader victory. As generations passed, direct memories of World War II naturally receded.43 Furthermore, many veterans, grappling with combat stress and what is now understood as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), often chose not to speak about their wartime experiences, contributing to a broader societal silence around such events for decades.46 This collective silence allowed many significant, yet less celebrated, stories to recede from public discourse, demonstrating how historical memory is constructed and prioritized.

The peaceful waters off Point Judith today still hold the echoes of a fierce battle, a reminder that history often lies just beneath the surface.

Postcard Details

Subject: Point Judith Lighthouse and Coast Guard Station, Narragansett, Washington County, Rhode Island.

Publisher: Berger Bros., Providence, Rhode Island.

Photographer: Arthur Berger.

Postmark Date: July 31, 1961.

Stamp: 3 cent Liberty stamp.

Message Excerpt: "From Alaska to Rhode Island I guess one can't go much further East. We are only a few miles from several ocean beaches and there is a fresh water pond right on the campus so we have every opportunity to swim and sunbathe. Howard is taking lessons at the pond and has several boy friends in our student apartment building. Albert has learned to walk while here! He reminds me of the mechanical dolls that pop out of coo-coo clocks. Love, B."

Support this research by purchasing the featured postcard or subscribing for more stories: Point Judith Lighthouse Coast Guard Station Postcard Narragansett Washington Cty

Works cited

Point Judith Lighthouse and Nearby Attractions in Narragansett, Rhode Island, accessed July 12, 2025, https://nelights.com/exploring/rhode_island/point_judith_lighthouse.html

Point Judith Lighthouse, Narragansett, Rhode Island, 1857, accessed July 12, 2025, https://lighthouse-index.com/country/united%20states/point-judith-lighthouse-narragansett-rhode-island-1857-JnLkehhjfmek

Point Judith Station House - US Life-Saving Service Heritage Association, accessed July 12, 2025, https://uslife-savingservice.org/station-buildings/point-judith-station-house-2/

Station Point Judith, Rhode Island - US Coast Guard Historian's Office, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Assets/Land/All/Article/2671895/station-point-judith-rhode-island/

German U-Boat U-853 Stripped of Some of Its Major Artifacts - Online Review of Rhode Island History, accessed July 12, 2025, http://smallstatebighistory.com/german-u-boat-u-853-stripped-of-some-of-its-major-artifacts/

U-853 - New Jersey Scuba Diving, accessed July 12, 2025, https://njscuba.net/dive-sites/new-york-dive-sites/long-island-east-chart/u-853/

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: The Fate of U-853 After Its Sinking; Bodies—and Bones—are Removed; What Happened to Hoffman's Body? - Online Review of Rhode Island History, accessed July 12, 2025, https://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-the-fate-of-u-853-after-its-sinking-bodies-and-bones-are-removed-what-happened-to-hoffmans-body/

The Type IXC/40 U-boat U-853 - German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net, accessed July 12, 2025, https://uboat.net/boats/u853.htm

A piece of history: German U-boat wreck sits near Rhode Island shore | News, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.reviewjournal.com/news/a-piece-of-history-german-u-boat-wreck-sits-near-rhode-island-shore/

THE WRECK OF U-853 AND WHY IT'S A GERMAN WAR GRAVE : r/Shipwrecks - Reddit, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Shipwrecks/comments/1f7mxf1/the_wreck_of_u853_and_why_its_a_german_war_grave/

THE BATTLE OF POINT JUDITH - Block Island Ferry, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.blockislandferry.com/the-battle-of-point-judith/

U-853 Wreck - Fishing Status, accessed July 12, 2025, https://fishingstatus.com/home/details/indexid/217245

Kill and Be Killed? The U-853 Mystery | Naval History Magazine, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2008/june/kill-and-be-killed-u-853-mystery

The U-853 and Black Point: Mapping and Assessing Rhode Island's Historic Submarines Using Synthetic Aperture Sonar - NOAA Ocean Exploration, accessed July 12, 2025, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/technology/development-partnerships/18kraken/u853-blackpoint/u853-blackpoint.html

The Mystery of U-853 – All U-Boats Had Orders to Surrender; Why ..., accessed July 12, 2025, https://militaryhistorynow.com/2020/12/15/the-hunt-for-u-853-the-mystery-of-the-last-german-submarine-destroyed-by-the-u-s-navy-in-ww2-2-2/

Black Point - New Jersey Scuba Diving, accessed July 12, 2025, https://njscuba.net/dive-sites/new-york-dive-sites/long-island-east-chart/black-point/

U-853 and her crew. During the final months of WWII U-853 was sent to the East Coast of the United States on patrol. She was destroyed off the coast of Rhode Island, one day before Germany surrendered, during the Battle of Point Judith, one of the final engagements of the Battle of the Atlantic - Reddit, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/wwiipics/comments/y389q0/u853_and_her_crew_during_the_final_months_of_wwii/

German submarine U-853 - Wikipedia, accessed July 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_submarine_U-853

U-853 under Helmut Frömsdorf, sank Black Point off Rhode Island after armistice, USS Eagle off Portland Maine - Eric Wiberg, accessed July 12, 2025, https://ericwiberg.com/2015/10/u-853-under-helmut-fromsdorf-sank-black-point-off-rhode-island-after-armistice-uss-eagle-off-portland-maine

Navy vessel sunk by German sub in WWII finally found - Navy Times, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/07/18/navy-vessel-sunk-by-german-sub-in-wwii-finally-found/

Mystery of the U-853 - Long Island Boating World, accessed July 12, 2025, https://liboatingworld.com/mystery-of-the-u-853/

U-853 (wreck), Rhode Island Sound - iDive New England, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.idivenewengland.com/dive-sites/ri/u-853

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: German U-Boat Sinks U.S. Coal Vessel - Online Review of Rhode Island History, accessed July 12, 2025, https://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-german-u-boat-sinks-u-s-coal-vessel/

SS Black Point sunk Point Judith RI last week of WWII vs. Germans by U-853 off Point Judith, Rhode Island May 5, 1945 - Eric Wiberg, accessed July 12, 2025, https://ericwiberg.com/2017/01/ss-black-point-sunk-point-judith-ri-last-week-of-wwii-vs-germans-by-u-853-off-point-judith-rhode-island-may-5-1945

Bob Cembrola: The battle of Point Judith - What's Up Newp, accessed July 12, 2025, https://whatsupnewp.com/2025/01/bob-cembrola-the-battle-of-point-judith/

The S.S. Black Point - The Historical Marker Database, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=76004

Crewlist from Black Point (American steam merchant) - Ships hit by German U-boats during WWII - uboat.net, accessed July 12, 2025, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/crews/ship3509.html

“Under Guard: A Case Study of the S.S. Black Point and U-853 for the Production of Comprehensive War Memorials” – Center for the Humanities - The University of Rhode Island, accessed July 12, 2025, https://web.uri.edu/humanities/under-guard-a-case-study-of-the-s-s-black-point-and-u-853-for-the-production-of-comprehensive-war-memorials/

USS Atherton - Wikipedia, accessed July 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Atherton

H12009_DR.pdf, accessed July 12, 2025, https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1005_p/data/pdfs/H12009_DR.pdf

USS Ericsson - OoCities.org, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.oocities.org/bensonclass/eric853.html

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: U.S. Navy and ..., accessed July 12, 2025, https://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-u-s-navy-and-coast-guard-warships-sink-u-853/

USS Moberly, PF-63 - US Coast Guard Historian's Office, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Assets/Water/All/Other-Vessels-Non-CG/Article/2554219/uss-moberly-pf-63/

Last Chapter For U-853 | Proceedings - December 1960 Vol. 86/12/694 - U.S. Naval Institute, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1960/december/last-chapter-u-853

USS Moberly, PF-63 - U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Assets/Water/All/Article/2554219/uss-moberly-pf-63/

Scientists Explore Wreck of Sunken U-Boat off Rhode Island - SUBSIM Radio Room Forums, accessed July 12, 2025, https://subsim.com/radioroom//showthread.php?p=2342009

26-G-4556: Sinking of German U-boat, U-853, May 1945, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-atlantic/battle-of-the-atlantic/engagements-german-uboats/1945-attacks-german/sinking-german-u-boat-u-853-1945-may-6/36-g-4556.html

K-Ships vs. U-Boats | National Air and Space Museum, accessed July 12, 2025, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/k-ships-vs-u-boats

Re: U-853 Crew List - uboat.net, accessed July 12, 2025, https://uboat.net/forums/read.php?3,41246,41255

Atherton (DE-169) - Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/a/atherton.html

U-853 - Hunting New England Shipwrecks, accessed July 12, 2025, https://wreckhunter.net/DataPages/u853-dat.htm

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith: The Fate of U-853 After Its Sinking; Bodies—and Bones—are Removed; What Happened to Hoffman's Body? - Online Review of Rhode Island History, accessed July 12, 2025, http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-75th-anniversary-of-the-battle-of-point-judith-the-fate-of-u-853-after-its-sinking-bodies-and-bones-are-removed-what-happened-to-hoffmans-body/

Culture of remembrance 80 Years After: War Memories Fading? - Goethe-Institut, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.goethe.de/prj/zei/en/art/26647661.html

en.wikipedia.org, accessed July 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Point_Judith#:~:text=The%20Battle%20of%20Point%20Judith,having%20already%20died%20by%20suicide.

Exploring World War II's Battle of the Atlantic: PART 2 | Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, accessed July 12, 2025, https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/nov16/exploring-wwii-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-2.html

WWII Post-Traumatic Stress | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, accessed July 12, 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/wwii-post-traumatic-stress